Epistemic (Ir)relevance, Language & Passport Positionality The Three Hurdles I’m Navigating as a UK-Based Ethiopian Academic

By Eyob Balcha Gebremariam, University of Bristol

This story has also been published on the EADI Blog

I write this reflection piece to use my personal experiences as a UK-based academic with an Ethiopian passport as a lens to comment on the structural power asymmetries of the academic landscape. I believe I’m not the only one facing these challenges. However, there is hardly sufficient attention, recognition, and space to discuss them. I have no intention of reducing the importance of other challenges by focusing on these three topics. I focused on the three hurdles because I experience them in everyday scholarly work and am determined to engage in critical discussions and reflections.

I often engage with the notion of coloniality when I comment on power asymmetries in academic knowledge production. Coloniality is too abstract for some people, whereas it has become a buzzword for others. However, for people like me, coloniality captures the challenges and obstacles of everyday life encounters. For many of us, it is a daily lived experience. In this piece, I aim to offer a personal reflexive account of coloniality based on the multiple positionalities I occupy.

Epistemic (Ir)relevance

In my academic career, I’m constantly conversing with myself about how relevant my work is to my community in Ethiopia. I was born and raised in Ethiopia. I always want to measure the relevance of my academic career with a potentially positive contribution to policy ideas and practices at least in the Ethiopian context. This means I must develop a strategy to help me reach more Ethiopian audiences. However, the challenge is enormous, and I always need a thoughtful approach to overcome it.

In my field of studies and Development Studies in general, the higher I go in my academic career, the more incentives I have to remain disconnected and alienated from the community I want to serve. I will be more rewarded if I continue to produce academic outputs that target an audience completely distant from most Ethiopians. Even members of the Ethiopian community who may access my work, if interested at all, have minimal access to academic publications. I’m glad most of my outputs so far are open access. However, the fact that the academic outputs are not initially produced to be consumed by the community about whom the research is talking remains a significant challenge. Making academic outputs available free of charge on the Internet is one viable solution. However, this can also have its own layers of challenges, such as the difficulty of accessing academic English for the general public.

One strategy I’ve adopted is to write Amharic newspaper articles that help me translate some of the expertise I acquired in my studies into a relevant analysis of the present-day political economy in Ethiopia. I am unsure to what extent my effort in writing Amharic commentaries can help me be more relevant to my community. These seemingly simple steps of translation can be valuable. But epistemic (ir)relevance is broader than language translation.

Using language as a medium of communication is one aspect. However, language is also a repository of a society’s deep conceptual, theoretical and philosophical orientations. The epistemic irrelevance of my academic work is more manifested in my limitations in adequately and systematically using my mother tongue to explain key issues of development that could be relevant to my community and beyond.

Most of the conceptual and theoretical insights that inform my academic works on Ethiopian political, economic and social dynamics are alien to the local context. On the other hand, throughout my educational training, I have not been adequately exposed to Ethiopia or Africa-centred knowledge frameworks and academic conceptual and theoretical orientations. Whenever this happened, they were not systematically integrated or implicitly considered less relevant than Eurocentric epistemic insights. I needed to put extra effort into reading widely to educate myself beyond the formal channels and processes of education. However, the impact remains immense. The more I continued to advance in my academic career, the more I gravitated away from Ethiopia-centred epistemic orientations. Hence, most of my academic insight remains less informed by these perspectives.

I want to emphasise that my concern is primarily about the systemic hierarchy of knowledge frameworks and the casual normalisation of marginalising endogenous and potentially alternative epistemic orientations. No knowledge can evolve without interaction with other knowledge systems. However, we can’t ignore that the interaction between knowledge systems is power-mediated. The power asymmetries between knowledge systems do not stop at the abstract level. They also translate into the institutional arrangements of knowledge production, the producers and primary audiences of the knowledge produced.

[Academic] knowledge is power! But not every [academic] knowledge can be a source of power. Most of the time, academic knowledge becomes a source of power if it is produced by the dominant members of society and for the use of the dominant members.

Language

Amharic is my mother tongue. Several languages in Ethiopia have well-advanced grammar, literature and folklore. Like other places, these languages are sources of wisdom and knowledge for society. However, none are adequately recognised as good enough in the organisation of the “modern” education system, especially in higher education. After primary school, I studied every subject in English. Amharic remained only as one subject. When I joined Addis Ababa University, Amharic became non-existent in my academic training. Only students who studied the Amharic language and literature used this language as their medium of instruction. All other degree programmes were in English. This might be less concerning if a language is not advanced enough to develop fields of studies and disciplinary knowledge with abstract conceptions and ideas. However, I believe the Amharic language can serve as a medium of instruction for most fields of study, especially in the social sciences.

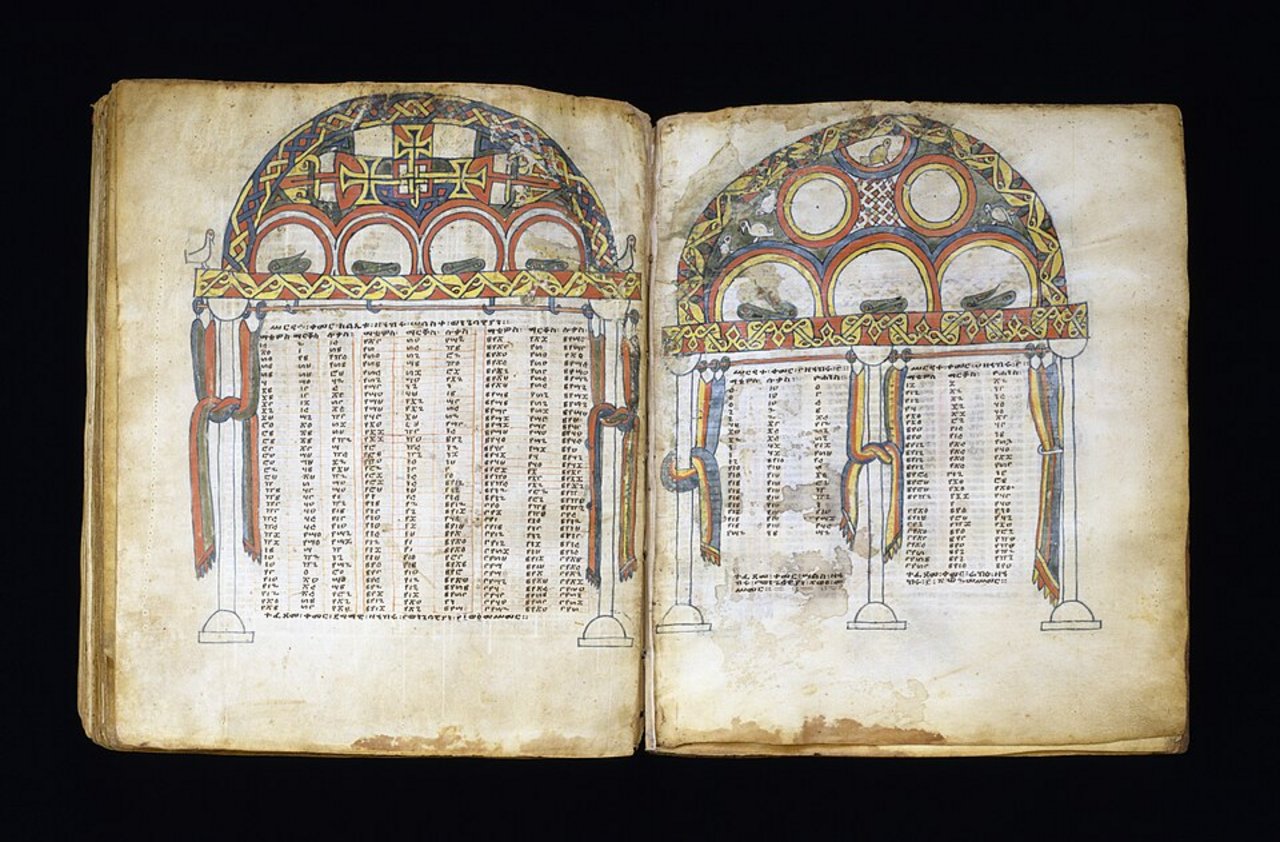

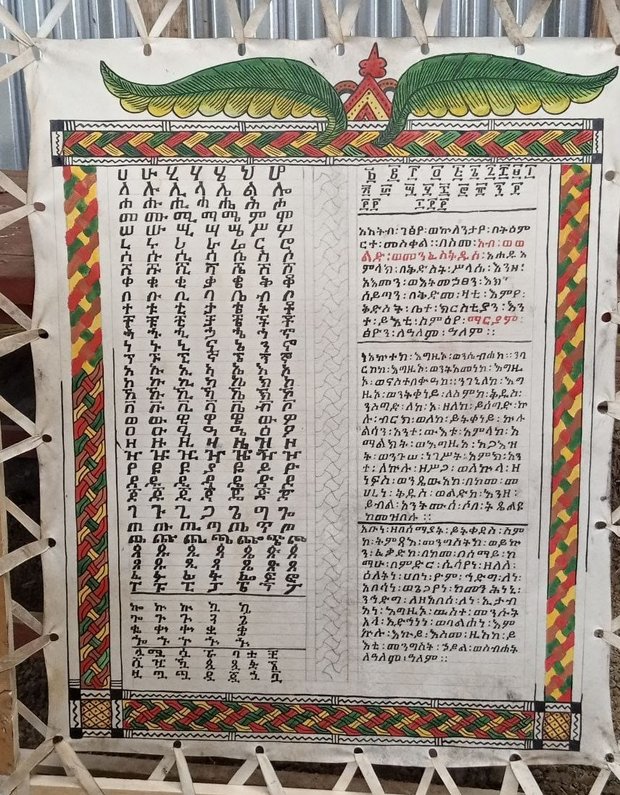

Studies show that the Amharic language evolved over 1,000 years and became a lingua franca of medieval northern and central highland kingdoms in present-day Ethiopia around the 12th century. The earliest literary tradition dates back to the 14th century, including religious texts, historical notes, and literature. Despite this, the modernist Ethiopian elites that designed the “modern” Ethiopian education system could not envision reaching the promised land of Westernisation without fully embracing English, in some cases French, and systematically disregarding their rich local languages.

The relationship between epistemic (ir)relevance and language is profound. To be more relevant to my community, I need to communicate in an accessible language and use language as a source of intellectual insights. This could be the most fulfilling academic endeavour. However, to remain a credible member of the academic community of my field, I must produce more in English, and the target audience should not necessarily be my home country community. To remain relevant to my home community, I need to adopt a different set of epistemic orientations, personal convictions and beliefs, and, sometimes, career and financial sacrifices. The additional burden and financial sacrifice are more prominent because it is doubtful that the current academic excellence and achievement framework in the UK or internationally will recognise academic output produced in non-European languages. I’m glad to learn more if there is anything I’m unaware of.

Passport positionality

My idea of passport positionality evolved through my experiences of travelling for academic purposes both across Europe and Africa. My definition of passport positionality is how academics at any level, primarily those with a “Global South” passport, must navigate various ideological, legal, administrative, financial, and psychological barriers to attend academic events or conduct research in countries other than their own. Understanding the interplay between legal and academic citizenship can help us reflect on the implicit and explicit barriers to belonging, exclusion, recognition and representation. The legacies and current manifestations of colonialism create some forms of exclusion, favouring mainly Global North passport holders. The exclusion of academic researchers from various platforms and spaces of academic deliberations and decision-making processes just because of the barriers imposed on their legal citizenship is a serious structural problem.

At a personal level, I’ve heard several stories of racial profiling, especially in cases where the global south passport overlaps with brown and black skin colour, humiliating interrogation and unjustified and unreasonable excuses of mistreatment. I share two personal experiences of how passport positionality shapes my travel experiences by creating tension between my academic and legal citizenship.

The first experience happened when I was contracted to facilitate a decolonial research methodologies workshop for an institute in a European country. The agreement was for the research institute to reimburse my travel expenses and to pay me a professional fee. As an Ethiopian passport holder, getting a Schengen visa to travel from the UK at a minimum includes travelling to privately run visa application centres and paying admin and visa application fees. This is on top of preparing a visa application document, where I’m expected to submit at least a three-month bank statement showing a minimum of £600 in my current bank account.

The most infuriating experience was finding the right appointment date and time because the private company only offers regular appointment options at certain hours. Otherwise, applicants are directly or indirectly forced to pay for more expensive premium appointment options. The company runs the visa appointment service to make a profit, so it has all the incentives to capitalise on potential customers’ demands. If seen from the position of potential travellers like me, it is unfair because the company is making money not by facilitating the visa application process but by making it less convenient and difficult.

I managed to get the visa and run a successful and enriching workshop. However, when I submitted my receipts for reimbursement, the institute refused to reimburse all the costs related to my visa application. I was told that according to the country’s “travel expenses act, they [the visa related cost] are not costs that can be covered.” Honestly speaking, the visa-related expenses were higher than the travel expenses. I believe there are reasonable grounds for the mentioned policy. However, it is also clear that the policy has a significant blind spot. It does not recognise the challenges that people like me face, jumping multiple hurdles to do their work. Perhaps the people who drafted the policy could not imagine that a visa-paying national would travel to their country to provide a professional service. Hence, no mechanism of reimbursement was set. I used the email exchange with my contacts to highlight the system’s unfairness. Finally, I got reimbursed, and it was a good learning experience.

The second experience I want to share is related to my encounters with border officials at South African airports. Because of my work, I travelled to South Africa seven times over the past three years. Out of these seven travels, I was held at the airport five times for at least one hour or more by border officials who wanted to check the genuineness of my visa. A uniformed officer usually escorts me. When I leave the plane, I will be told they have been waiting for me and will check my documents’ credibility. Often, as I’m told, they’ll take a picture of the visa sticker on my passport and send it to their colleagues in London via WhatsApp to verify whether it is genuine. In the meantime, I will be asked several questions about the reason for my travel, what I do, how I received my visa in London, while I’m an Ethiopian, etc. Some valid and ordinary questions, but some unreasonable questions as well. None of this has happened to me in my travels to other countries.

After some time, I got used to it and plan accordingly. But it never stops being a significant inconvenience to be singled out just because of my passport. On one of these trips, I was travelling with my fellow UK-based Ethiopian academic, and I bet with him that we’d be escorted to a room and interrogated on our arrival. I won the bet. The border official even showed us the screen shot he was sent with our names, two Ethiopian passport holders, who needed to be cross-examined before being allowed to enter the country.

I share these experiences to encourage my academic colleagues to be conscious of their passport positionality and how it helped or constrained them to exercise their academic citizenship. The interplay between legal and academic citizenship needs more reflexive discussions.

Conclusion

I hope sharing these three hurdles of lived experiences can trigger questions, responses, and conversations. There are no simple answers and responses. However, I think it is essential to be aware that some of the buzzwords and abstract ideas we exchange in our academic conversations can lead to experiences far from abstract notions. Hopefully, my moments of internal struggles of questioning relevance, feelings of alienation, efforts of learning and unlearning and the actual experiences of exclusion, especially when travelling, can contribute to having more grounded conversations when we talk about decolonising academic knowledge production in Development Studies.

Eyob Balcha Gebremariam is a Research Associate at the Perivoli Africa Research Centre (PARC), the University of Bristol and a Visiting Research Fellow at the Institute for Humanities in Africa (HUMA), University of Cape Town (UCT). He is a Member of Council at the Development Studies Association (DSA) of the UK and of EADI’s task group on decolonising knowledge in Development Studies.