Mehrheimisch: Weaving Our Stories/Identities As We Go By

By Rhina Colunge-Peters

My name is Rhina Colunge-Peters, and I feel “mehrheimisch”. It means belonging not only to one place, socio-cultural space, or even one professional /academic discipline. I feel my identity is a dynamic entangled process, an identity embedded in a wider tissue of social and human relationships.

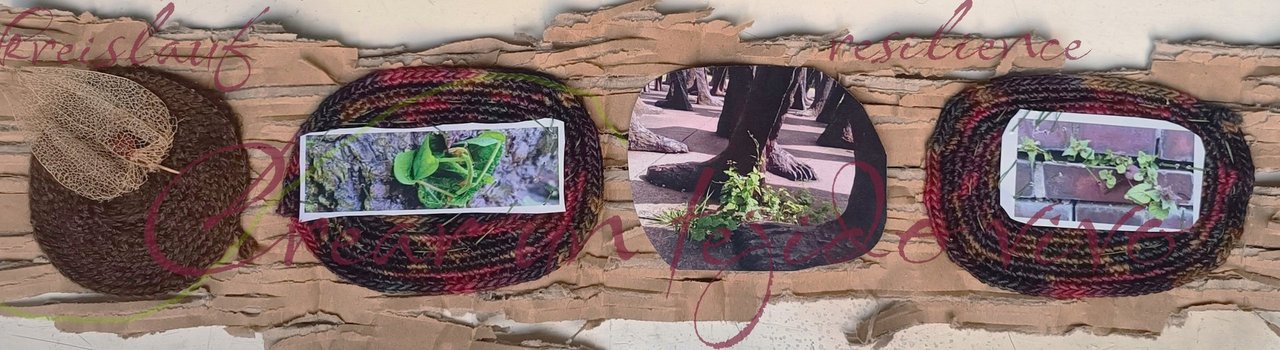

My quest to explore connection was also my motivation to share my story as an eclectic “Wollknoll” (wool yarn ball) to further weave it collectively with anyone, who feels like it.

I am convinced that not only a paradigm shift in the education system is necessary, but one that fundamentally involves all of us, the whole of society. In my opinion, a real eco-social transformation is only possible if the seeds of life and creativity in all of us are touched, in contact with our living outer and inner worlds. I am searching for ways of approaching different understandings of sustainability and wellbeing in their local and global entanglement, linking (higher) education and research, with indigenous and community knowledge; transferring the results of these synergies among and with different civil individual and institutional actors.

Furthermore, I would like to invite readers to a deeper reflection of what “higher” education means, and how academics and economic elites value hierarchical structures and titles that may be quite discriminating and excluding. Do these hierarchies create more divisions, more isolation and more conflict in society? Do we value and rely more on academic titles, merits and awards than in wisdom, diversity of (non-empirical) knowledges and daring spirit for unlearning, creativity of each of us, including non-human beings?

“A qué grupo étnico perteneces (To which ethnic group do you belong)?”

I don´t know if that was the exact wording. I just remember feeling lost and “desraizada”,”entwurzelt”; i.e., as a plant being uprooted all of the sudden, when I heard this question. It was the first question at the start of a conversation with an indigenous leader from an Inga community. I had the feeling that for him, I needed the name of the ethnic group that validates me as an “indigenous” allowing me to talk or exchange ideas about anything related to “indigenous knowledge, learnings or wisdom”. I don’t have this validation, a specific denomination, still. And at that moment, I felt a pain piercing my heart and I felt being ‘out of place’ again. Especially because my intention was to exchange ideas about “reconnection” with oneself, with others and with (what modernity calls) “nature”. I wanted to share with him what Sumak Kawsay (Alli Kawsay or Allin Kawsay), Buen Vivir in Spanish, or Good Livelihood literally translated, although not possible to “translate” as such) meant to me, in my diaspora, my sentipensar (feeling/thinking) related to my quest to reconnect with what I learnt to call in my childhood Mamapacha (Mother Earth).

No, I don´t speak Quechua, because I was deprived from it; my whole school and university education didn´t provide me with more than a few Quechua words in History classes. Nor can I say, whether I belong to a specific ethnic group or community, since I grew up in urban and semi-urban settings. I just know and feel, a great part of me belongs strongly to the Andes eco-social, cultural and spiritual space. Would it be useful to say that according to an Ancestry DNA analysis ca. 62% part of me is indigenous from Peruvian Andes?

No, I am not indigenous enough to talk about climate justice, to engage myself in the reconnection with my roots, without leaving the possibility to migrate as “Löwenzahn” seeds (diente de león or dandelion) do, being dispersed without barriers?

Neither indigenous nor white - Neither Peruvian nor German

Aren´t we all an entanglement of communities, pasts, and biographies in constant becoming, and transforming thanks to the interactions with each other? Un crisol de culturas, a cultural melting pot at individual level and not only as a society or community?

My journey as a seed of dandelion or perhaps a Galisonga or Kapuzinerkresse (nasturtium) started in the Andes of Peru. Just close your eyes and imagine it! Snow peaks that are living and transform into water, which in turn transforms into ichu (Andean gras) and other amazing array of plants, which nurture alpacas, llamas and sheep and thus are transforming into wool and many other living materials. These are at the same time feeding and warming us, protecting us and giving us resilience in a continuous cycle of life. A life cycle which for me refers to good living and good dying.

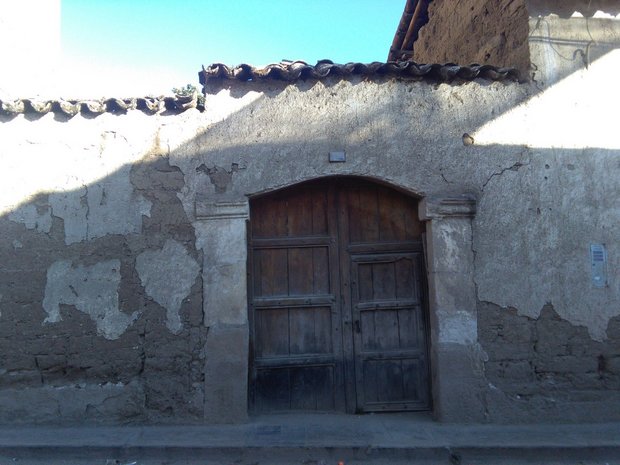

The place I was born, Cerro de Pasco, was unfortunately close to one of the most polluted places on the earth, a huge mining centre of silver, copper, zinc and lead. For me, it is like a huge cancer wound, very deep in the highest city of the world. A superlative of the dark side of what I learnt to call “development” in my formal education. It feels as a cancer, which metastasis is spreading worldwide.

Which place or space may I call “Heimat”, “home”, “my nest” now? After a very long and meander-shaped journey from 4,000 meters above sea level to Northern Germany?

Is it possible to have a home, when we are travellers? In my daily journey I am trying to bridge the gap between my professional and personal life, my every minute being and becoming. Among others, this quest, made me reflect on what we do refer to as “global citizenship” in education? Is this possible? What provides us with a sense of belonging, protection and resilience? Is this not also a human right? To feel and be part of a community, or something higher and even “non-human”.

To be part of…

Whom or what am I part of, affiliated to or what is my “label”? Interestingly the question is also asked in professional contexts: your academic affiliation? In the academic world, I also learnt, especially wanting to be part of a conversation, to present different insights, and question usual ways of doing, having no affiliation may be a stigma. This academic world showed me an array of classifications and labels to different degrees and colours, systematically and hierarchically sorted.

What I found/feel the most imprisoning /limiting and in a way colonising in my education in, the “western”, post-industrial Global North, was “labelling”: creating more and more “labels” for movements, theories, positions, identities, opinions, and just name some of them. More silos, more drawers in a hierarchical system more division, “possessing” and fixing instead of daring fluidity and a new way to (un)learn and co-learn and to create more linkages, bridges and intersections.

To feel embedded and entangled in my nest, I went back to the beginning of my journey in the Andes, I remember being cared for by my dear Juanita, an indigenous woman, while my parents worked. Juanita´s stories were about Apus and Cochas, i.e. mountains and water sources as being living Tinkuy (in Quechua: sacred encounter points). Indeed, for me they were living beings, they were more than a playground in my childhood, which gave me a sense of freedom and made me feel part of living blue space.

On the other side, my migrant childhood in the mountains and urban contexts of the Andes and Lima is splashed with memories of geography schoolbooks that mapped the world in a certain way, and glorified for example “intensive agriculture”. I never read about “milpa” at school, about the three wonderful sisters, but I loved running around in the farm of my step-grandfather in Andahuaylas, in the midst of mixed “non-intensive” farms cultivating maize, squash and beans. They were a delightful experience for me, since I felt part of a wider living web. This was also what I felt two years ago: when I read that another person on the other side of the Atlantic felt and cherished these three sisters. Reading Robin Wall Kimmerer´s “Braiding Sweetgrass” (2013) was “being connected” with somebody I haven´t met before on my journey, and it was the first book from the Academia Circle of the Global North, that inspired, motivated me; and made me feel finally “part of”.

“Woher kommst Du…eigentlich”? - where do you come from actually?

Where do I really come from? Really? I was born in Peru and have a German passport. -“Quite easy to answer”- you may think. No, not for me. I´m sitting in a park after just collecting blackberries, and while I picked blakberries, I heard the wind, felt it seep through my skin, heard the Specht (the woodpecker), looked it in the eyes, and for a whole second, I felt I was part of a whole universe together with it. I belong to something wider. The language I learnt at home, at school and at the university didn´t provide me with the words I needed to express, where I come from, neither to name or describe this kind of “belonging”. In German Anthropology, academics talk about “Mitwelt” (being completely embedded the environmental tissue).

Following a non-linear journey, I found the way to my roots: Buen Vivir or Sumak Kawsay, even if I no longer belong to a direct “indigenous” ethnic group. As a diaspora of the Andes, with mixed biographic, cultural and social heritage, I accepted to feel and think, to live and to write or conceptualise my sentipensar of Buen Vivir.

As already mentioned, my parents did not speak Quechua with me, even though my father learnt the language through seasonal indigenous workers, who became friends of him during his childhood and youth. I never told him that the most cherished heritage he gave me was not access higher education, or English classes paid by his hard work and savings, which opened the possibility to access grants and scholarships. The most cherished knowledge he gave me, was the intimate connection to nature, people and everything that is alive in the Andes, that he also learnt in a childhood full of hardships. Exactly those discriminated against in this system of labels and hierarchical classification offered me learnings that provided me with resilience and openness to different kind of knowledge and wisdom. In my opinion, this kind of wisdom is present all over the world.

An important moment of my personal journey that brought me closer to home was the invitation to participate in the International Festival of Philosophy in Hannover, by an artist and wise woman. Assunta asked me to share my perspective, as a person of the Andean. I hoped, I wouldn´t disappoint the public, I am not an expert or a cultural anthropologist with a PhD title or a Lecture Chair, nor am I a direct representative of the Andean peoples or the Quechua in Germany. To be honest, I was afraid of allegations of cultural appropriation.

It was neither my intention to idealise or romanticise the Buen Vivir or the Andean way of life.

Why Buen Vivir?

When I was asked to contribute something on the main topic of "Where is time?" and “Is time money?” from a non-European perspective, Sumak Kawsay / Buen Vivir from the Andean region was my first thought. There have already been several attempts to translate and define it, and to bring together its many facets, such as balance with “nature”, the reduction of social inequality, an economy based on solidarity and a pluralistic democracy and so on. For many, it also stands as an alternative to the Western paradigm of prosperity and perpetual growth. For others, it is more a philosophy of life of the indigenous peoples of South America, which gives nature an intrinsic value and thus presents itself against the excessive exploitation and instrumentalization of nature as a resource.

For me, the great difficulty in translating the Buen Vivir "concept" is precisely approaching it as a “concept” and ignoring its temporal, intangible and dynamic relational dimensions. WE are used to - and I mean "we" as all who were embedded in a Western status quo education system - we are used to defining everything when we talk, write or discuss a topic scientifically.

I find it interesting that the very "definition" or attempt to find a "term" emphasises something static, something limited and thus limits our understanding of life as a process of change and transformation. And Buen Vivir is more than a holistic quality of life (noun) or good living in community, or a kind of indigenous Well Being Economy, and an Economy for the Common Good.

Buen Vivir as a verb

Buen Vivir is not a noun, but a verb "good living", noting that in Andean cosmovision death is part of the life cycle and part of a continuum of change. In my personal experience of Buen Vivir, the cycle is always intertwined with more complex systems and thus always combines spatial, temporal, social and spiritual dimensions. It is inscribed to a life cycle, in which to live well is as important as to die well in a natural flowing cyclical change. This refers not only to human life, but to all, from the "permaculture" in the Andes to traditional house building, where houses have a life cycle.

Buen Vivir as a (re-) Connecting path

For me Buen Vivir is cyclical, but always new. It means renewal and creation. Creation, emergence, inspireing creativity and strengthening resilience. From my diaspora perspective, I have experienced that whenever I get involved or can get involved in these connections. I don´t need to live in the Andes, but I can from “just here and now” admire the life cycle, learn in a kind of "flow" with and from “nature”. I do not feel lonely, instead I feel embedded, intertwined, especially when the experience is shared with others.

I feel part of what in my Christian cultural part is called "creation" and impregnated with seeds I want to continue sowing. And here, of course, I am not only speaking from the syncretism of the Andean region, but also from my mestizo and migrant perspective. This "giving and taking" corresponds very much to reciprocity value, I learnt in the Andes. Also, the urban Andes: I know it as Ayni since my childhood.

“Universality”?

This kind of reciprocity is strongly anchored in the Andean region as part of a modus vivendus of a society or socio-cultural group. Robin Wall Kimmerer calls it a "restorative reciprocity", an "appreciation of gifts and the responsibilities that come with them, and how gratitude can be medicine for our sick, capitalistic world."

"The awakening of ecological consciousness requires the recognition and celebration of our reciprocal relationship with the rest of the living world. For only when we can listen to the language of other beings will we be able to understand the generosity of the earth and learn to give our own gifts in return." (Robin Wall Kimmerer)

Personally, I think that all cultures over the world, offer us this supra-generational or timeless perception that allows us to connect with ourselves and the "Cosmic Metabolism" and its wisdoms. Wisdoms are alive and not rigid, have no monetary price, cannot be bought or sold. Examples are to find from Satish Kumar “Soul, Soil, Society” to Gaia Education. These deeply touching approaches can no longer be ignored by the different academic disciplines which are so fixed in empirical tools and methods, academic silos and divisions.

Thus, I don´t even need to be in the Andes to feel/perceive and sense this connection, not only with the earth but also with previous generations. More than 15 years ago, when I felt so far away of home in the flat landscape of Schleswig Holstein, I saw a prehistoric mould burial with a small tree on top of it which gave me the impression that the earth was pregnant. I had a similar strong feeling this year in a similar “landscape” constellation. And those are the moments in which rivers are no borders, mountain chains are neither barriers, nor “geographic” accidents, but connections between worlds that speak and wait for answers.

Time also bore a new perception during the COVID months: then I rediscovered and experienced this flow of connections. For example, as I stood below a large tree, leaning against it or embracing it, I felt a relationship not only to the tree, but also to all living things with the tree as a spatial/temporal "window" to all the people who have leaned on it, to have searched for consolation against its trunk/presence. I felt also connected to all the living beings that interacted with it and were interwoven in its ecosystem. Further, I felt connected with my family in Peru (the memory of my childhood), and with all the trees which served as childhood hiding places in the Plaza of Andahuaylas.

I do know that I am not alone in my journey: we are many and we are all over the world. Perhaps we just have to open our senses and unlearn to some extent what this educational system has provided us. We are invited to re-connect with what this educational system put aside, but is not dead! Giving and taking, letting go, being aware, becoming, turning into, working on ourselves, dealing with values, reflections, attitudes, processes in different dimensions.

I hope this essay, inspires, motivates and reconnects us at all levels: with ourselves, and all others, including the non-human, but definitely living connected tissue.

Rhina Colunge-Peters, born in Peru, and thanks grants and scholarships studies in Peru, the Netherlands and UK. Her area of work and interests are in topics related to transformational learning, linking sustainability in its local and lobal entanglement, linking (higher) education and research, with indigenous and community knowledge; transferring the results of these synergies among and with different civil individual and institutional actors.